For BOOKING please contact info@skeleton-man.com

According to Terror Management Theory (TMT) the awareness and terror of death has a profound and pervasive effect on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviours in almost every domain of human life – from what we eat to why we go to war.

How can this be so?

Managing the Terror of Death

Like all animals, humans are born with biological systems oriented towards self-preservation. Unlike other animals, however, we humans know that no matter what we do, sooner or later we will lose the battle against death. This is a profoundly unnerving thought. We will do just about anything to stay alive. Yet we live with the knowledge that this desire will inevitably be thwarted.

How we manage the terror of death

Man would not be able to act if he constantly worried about his inevitable demise and so he has to subdue this potentially devastating terror. This is done in two ways. Our shared cultural worldviews – the beliefs we create to explain the nature of reality to ourselves – give us a sense of meaning, an account for the origin of the universe, and a blueprint for valued conduct on earth. It also gives us a promise of immortality via the sense that we are part of something greater than ourselves that will continue long after we die.

The second vital resource for managing terror is a feeling of personal significance, commonly known as self-esteem. Self-esteem, no matter, if it comes from being the fastest runner in the world or the champion of the local pinball machine, enables each of us to believe we are enduring, significant beings.

These twin motives combine to protect us from the human fear of inevitable death.

Judging a prostitute

In one case study 22 judges were presented with a case of a prostitute that was to be fined for soliciting. The typical bail for this type of offense was USD 50 (which was also the bail set among the judges in the control group). But if the judges briefly before sentencing had been reminded of their own death the bail was set at USD 455 on average, more than nine times as much.

The judges were reminded of their own death with two questions. One asked “please briefly describe the emotions that the thought of your own death arouses in you” and the other “jot down, as specifically as you can, what you think will happen to you as you physically die, and once you are physically dead.”

Judges are supposed to be rational experts basing their rulings on the facts only – how did this happen? TMT will argue that the judges who had been reminded about their own mortality reacted by trying to do the right thing as prescribed by their culture. Accordingly, they upheld the law more vigorously and set a much higher bail ensuring a later trial.

The Scheme of Things

The scheme of things is a view of the world so deeply ingrained in us that virtually everything we think, feel, and do is shaped by it. It not only provides each of us with our knowledge and explanations about the world. It also supplies the fundamental structure of our conscious experience.

Its deepest roots lies in our early infancy where the primary source of psychological security is parental love and protection. To feel that we are good and valued develops our self-esteem – and especially so as infants.

As we grow up we are bombarded with signals about what is good and bad. Gradually we absorb these impressions into a cultural scheme of things and embrace this description of reality our parents and surroundings confer on us.

Around age three, death awareness begins to make her appearance and after a while, we grasp the horrible truth: Death is not just an unfortunate accident that occasionally befalls the aged. Death happens to everyone, including ourselves.

This realization is momentous. Once children understand that they, as well as their mothers and fathers are vulnerable and finite, they shift from their parents to their culture as their primary source of psychological equanimity. Deities and social authorities and institutions now appear to be more stable and enduring.

Rally round the flag

When Germans were interviewed in front of a retail shop they showed no particular preference for all things German, but when interviewed in front of a cemetery they preferred German cars and German vacation spots to foreign alternatives.

Another study showed that, when reminded of our mortality, we are reluctant to use items that are embedded with cultural significance for purposes that seems sacrilegeous, such as, using a crucifix as a hammer or a flag as a filter to separate coloured fluid.

Still, it is not enough to be equipped with our scheme of things. We humans feel fully secure only if we consider ourselves valuable contributors to the world we believe in.

Self-esteem: The Foundation of Fortitude

Self-esteem is the feeling that one is a valuable participant in a meaningful universe: I matter in a universe that matters. This feeling of personal significance is what keeps our deepest fears at bay. Whether we are called “doctor,” “lawyer,” or “beloved mother” doesn’t matter. As long as we live up to accepted cultural roles and values we feel safely embedded in a symbolic reality in which our identity helps us transcend the limits of our fleeing biological existence.

Self-esteem, therefore, is the foundation of psychological fortitude but it is more than a mere mental abstraction. Self-esteem is felt deeply and physically in our bodies. For instance, people who base their self-worth on physical strength generated a stronger handgrip or increased intentions to exercise after being reminded about death.

The scourge of low self-esteem

Self-esteem can break down in two ways. First, individuals, or groups of people, can lose faith in their cultural worldview, say, because of economic uncertainty, church and sports scandals or political polarization. Secondly, personal short comings with regards to cultural expectations, for instance, impossible beauty standards, can break down our self-esteem.

But because self-esteem protects people from their deepest fears, they will do just about anything to get it. The pursuit of self-esteem is a driving force behind just about everything that people want in life. As American philosopher William James (1842-1910) put it;

A man’s self is the total sum of all the things he can call his, not only his body and his psychic powers, but his clothes, and his house, his wife and children, his ancestors and friends, his reputation and works, his lands and horses, and yacht and bank-account. All these things give him the same emotions. If they grow and prosper, he feels triumphant; if they dwindle and die away, he feels cast down.

Summing up, the psychological nourishment we get from self-esteem is no less vital than the physical nourishment we get from our daily bread. Lacking self-esteem we are persistently apprehensive and prone to self-destructive and aggressive outbursts. Conversely, braced by self-esteem we are encouraged and enthusiastic.

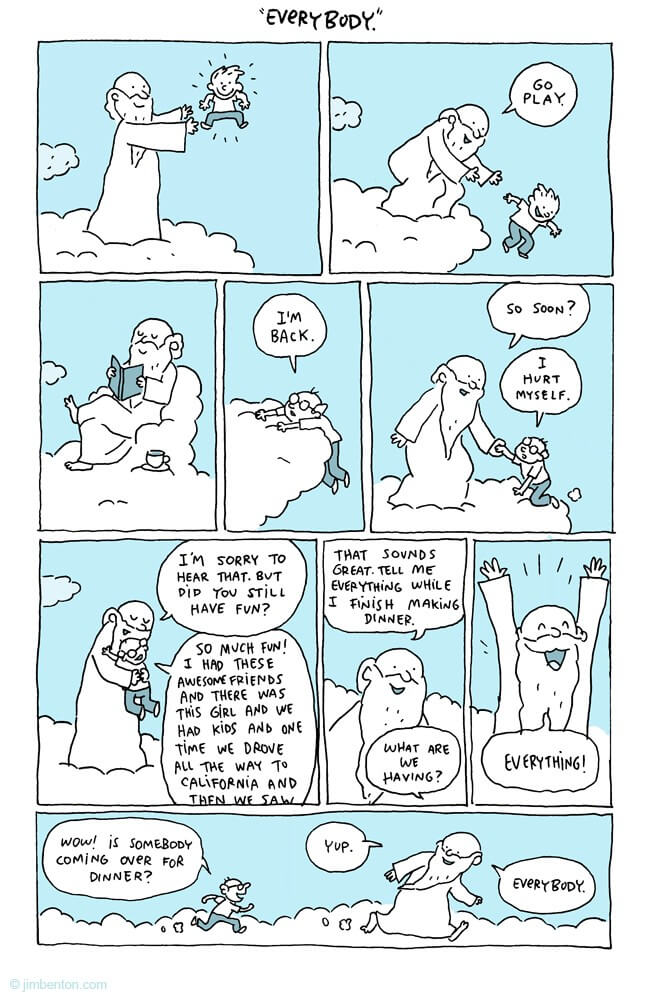

The invention of the supernatural

What happened when a life-form, created by billions of years of evolution to strive to survive at almost any cost, recognized that it was destined to lose that war?

As a naked fact, that realization is unacceptable, and so our ancestors used their imagination to create a supernatural world in which death was not inevitable or irrevocable.

First, they invented the idea of the soul that enabled humans to dodge death by perceiving themselves as more than just physical beings. Later, rituals were invented. These reinforced our beliefs while also becoming tangible signs that the invisible world really existed and the illusion that we can control it. Likewise, art, such as cave paintings, helped to make the incredible credible by offering concrete signs of a supernatural world.

As language further evolved our ancestors began using it to address the questions that must inevitably arise in self-conscious creatures: Who am I? Where did I come from? What is the meaning of life? What happens after I die? Now, narrative depictions of supernatural conceptions of reality, ie. myths, became possible and necessary.

Myths provide the narrative justification for rituals and, embellished by art, form religion, which serves to regulate all aspects of social behavior. Religions delienate how we should interact with and treat each other by providing a purposeful, moral conception of life in which individuals’ souls can exist beyond their physical death. And religion gave our ancestors – as it gives us – a sense of community and shared reality, a worldview that enabled large groups of humans to cooperate and coordinate activities.

Literal and Symbolic Immortality

People have pledged for literal immortality through alchemy, magical places, fruits and seeds, Taoism and other life styles since time memorial. In modern times, science wants to freeze the entire body or just the brain to reawaken the person/organs at a later date.

Moreover, people yearn for symbolic immortality. We want to leave a mark; we want to feel that something of us will persist beyond our physical death.

Paths to remembrance

One way to achieve symbolic immortality is through our family, either via genes or their memory of us. Fame, celebrity, and money are other routes. If you can afford the finer things in life, people pay attention to you. You feel special and valued – perhaps even by the Gods. Hence, your self-esteem, that critical bulwark against the fear of death, rises.

Researchers have found that after thinking about death people’s interest in owning a high-status, self-esteem-boosting luxury product rose. In another study Poles asked merely to count monetary notes rather than pieces of blank paper reported a reduced fear of death.

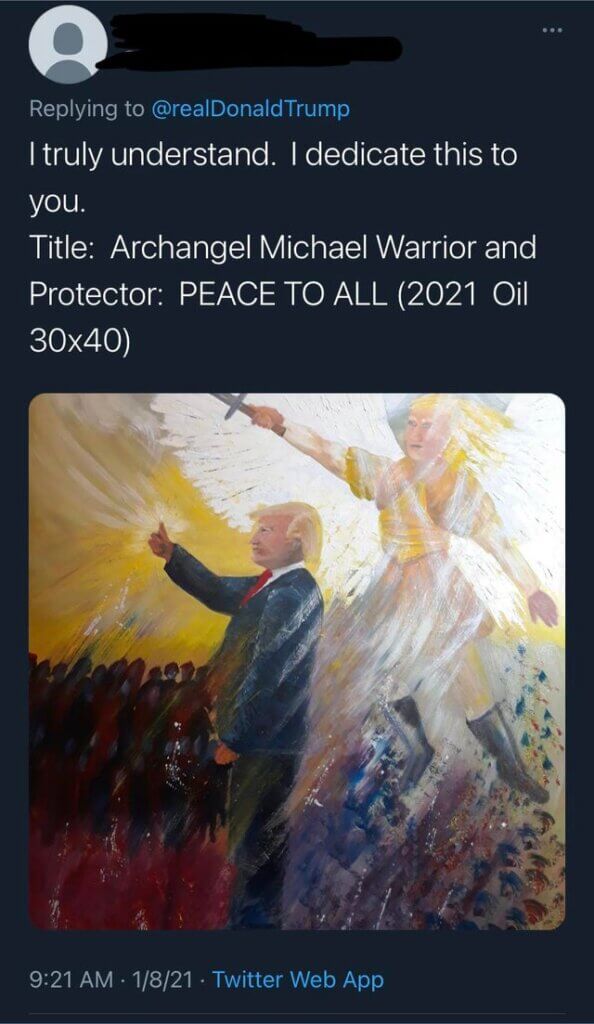

Heroic nationalism and charismatic leaders

Importantly, people also gain a sense of symbolic immortality from feeling that they are part of a heroic cause or a nation that will endure indefinitely. And nationalism acquires a sacred dimension when group identity is strengthened by the sense of being a “chosen people”, be it Judaism, der “Vaterland,” “The Land of the Free,” etc.

Moreover, during periods of historic upheaval when the traditional worldview is shaken, people’s allegiance may shift to a charismatic leader who exhibits an “unconflicted” personality. For instance, experiments showed that after reminders of death people were eight times more likely to vote for a person whose message was “you are not just ordinary citizens, you are parts of a special state and a special nation” rather than voting for a candidate whose message was one of “I encourage all citizens to take an active role in improving their state. I know that each individual can make a difference.”

Not only does this person strengthen our faith in our cultural worldview. Rooting for the charismatic, larger-than-life “chosen one” might also transfer some of his or her aura of invisibility and immortality on to us.

The Scary Other and Human Destructiveness

Preserving faith in our cultural worldview and self-esteem becomes challenging when we encounter others with different beliefs because acknowledging their “truths” inevitably calls ours into question. If the Aborigines’ belief, that magical ancestors metamorphosed into humans after becoming lizards, is credible, then the idea that God created the world in six days, and Adam in his image, must be suspect. Hence the savage obliteration of the Aborigines.

And the threat posed by different belief systems runs much deeper than mutually exclusive creation stories. The threat comes from everything that, one way or another, questions our meanings and purposes. So we must parry the threat in a number of ways.

Derogation and dehumanization

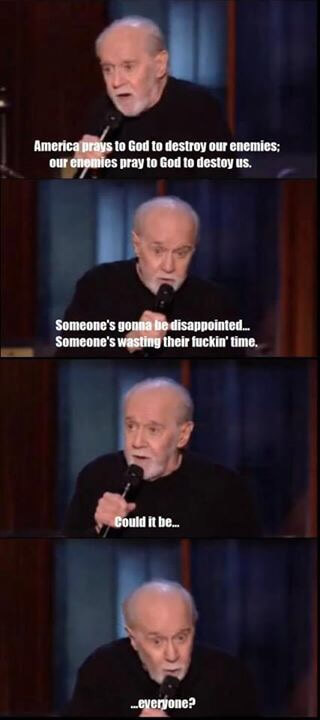

Our first line of psychological defense against those whose conceptions of reality are different from our own is to derogate or belittle them. This tendency to belittle others is particularly pronounced in the wake of death reminders. Studies have demonstrated that after pondering their mortality, Christians denigrate Jews, conservatives condemn liberals, Italians despise Germans, and people everywhere ridicule immigrants.

The second line of defense is to show these ignorant, misguided, or sinful people the light and assimilate them into our worldview. Or we can “tame” the views we find threatening by incorporating attractive aspects of them into our own cultural worldview.

If these tactics don’t work we can eliminate the threatening other entirely. Whatever threatens our worldview: Famines, economic upheaval, youthful insubordination – you name it: it’s their fault.

The disquieting point is that because people need some tangible and potentially controllable cause of their residual death anxiety, they will identify or create different “others” to serve this purpose. “If we could only get rid of …, then all our problems would be solved!”

Again, studies show that reminders of mortality led Israelis to view violence against the Palestinians as more justified as was the support of a preemptive nuclear attack on Iran. Converserly, Iranian college students increased their support for martyrdom attacks on the United States. They also showed more interest in becoming suicide bombers themselves.

Body and Soul: An Uneasy Alliance

Death cannot be banished so easily when we are conscious of our own creaturely nature. So we must set ourselves apart from animals and transform our bodies into cultural symbols of beauty and power that obscures our animality as physical creatures destined to die. The fig leaf was the first body adornment. Then came makeup and skin care, plastic surgery, ornamental rings to elongate necks, head and feet shaping etc.

Sex, body and death

Sex poses a unique problem with regards to our death anxiety because sex is first and foremost a glaring reminder that we are animals; next to urination and defecation, it is the closest human beings come to acting like beasts. Sex and death is, therefore, intimately linked and we manage our death-fueled anxiety about sex by imbuing it with symbolic meanings, love and romance, transforming it from the creaturely to the sublime, thereby making it psychologically safer.

Likewise, birth and menstruation is too physical and reminds us too much of our animality. Thus, women are rated less likeable after a reminder of their cycle.

Death Near and Far

What happens when our cultural worldview or self-esteem cannot stop the thought of death from entering our mind?

Human beings use two distinct kinds of psychological defenses to cope with thoughts of death. When we are conscious of death (ie. right after being reminded of death), our proximal defenses are activated. These are rationalizing efforts to get rid of such thoughts, eg. repressing or distracting ourselves from uncomfortable thoughts, for instance, via incessant internet activity, eating, exercising, drinking, binge tv watching, various addictions etc.

In contrast, unconscious thoughts of death (ie. thoughts we have a little while after a death reminder) instigate our distal defenses. These defenses have no logical or semantic relation to the problem of death. For instance, being harsher on prostitutes, derogating others who repudiate our cultural values, or attempting to boost our self-esteem with a luxury item has little or no direct bearing on the brute fact that we will someday die. Nevertheless, such reactions muffle mortal terror because they support the belief that we will endure in some literal or symbolic form beyond our death.

Proximal and distal defenses explains why most people believe they don’t think about death or that they’re not affected by such thoughts. As you go about your day, proximal defenses enable you to distract yourself, or suppress or rationalize away the daily reminders of mortality – the bags under your eyes, the news of distant earthquakes and bombings, and so on.

Then back at your desk in the office, your distal defenses kick in. You daydream about getting the firm’s highest bonus this year and imagine your name on the plaque at company headquarters marking the achievement. Then you’ll be a significant person in a meaningful universe and become a viable candidate for transcending death via immortality.

Coming to Terms with Death

The rock and the hard place

No matter how we chose to grapple with our inevitable death, our thoughts, feelings, and actions are grounded within a culturally constructed scheme of things and some cultural worldviews guides us toward more constructive paths than others.

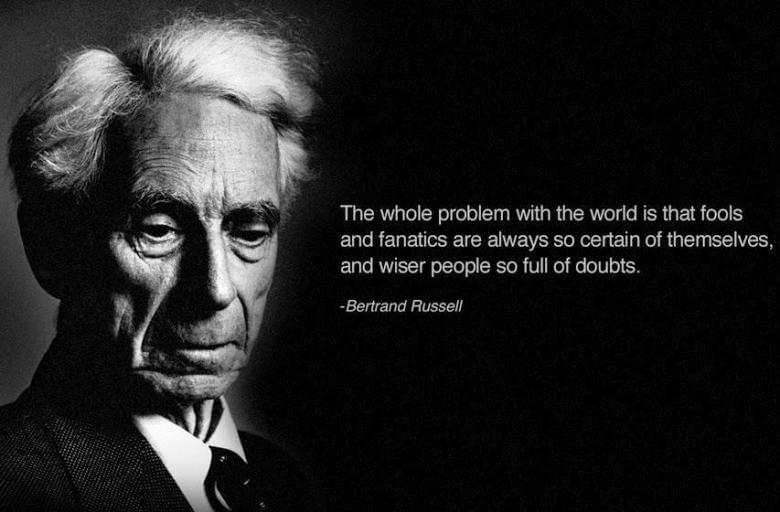

For some life is very simple. Things are either good or bad. There is no in between. Others find that things are almost never only good or bad. There is always some bad in good and some good in bad.

These perspectives reflect two different kinds of worldviews: The rock or the hard place.

The rock is a black-and-white scheme of things, with explicit prescriptions for attaining literal and symbolic immortality. This perspective affords seductive psychological security for those who follow it but also fosters an us vs. them mentality that inflames intergroup conflicts.

The hard place means accepting that meaning and values are human creations. Hence, we do not have to accept the vision of reality that others have given us and can strive for our own. But it is a challenging place to be, psychologically speaking. Anxiety prevails.

So we are caught. The rock provides psychological security but takes a terrible toll on those victimized by angry and self-righteous crusades to rid the world of evil. The hard place yields perhaps a more compassionate view of the world but is less effective at buffering death anxiety. Somehow we need to fashion worldviews that yield psychological security, like the rock, but also promote tolerance and acceptance of ambiguity, like the hard place.

So what do we do?

According to Irvin Yalom honestly facing the inevitability of aging and the decaying of the body is the surest sign of maturity. We must come to terms with death. Really grasp that being mortal, while terrifying, can also make our lives sublime by infusing us with courage, compassion, and concern for future generations.

Are you acting out of fear, or being manipulated to do so by others? Are you driven by rigid defenses, or are you pursuing the goals you really hold dear in your life? In dealing with other people, are you considering how their efforts to manage the terror of death are affecting their actions and how your own defenses are influencing your reactions to them? By asking and answering these questions, we can perhaps enhance our own enjoyment of life, enrich the lives of those around us, and have a beneficial impact beyond it.

Closing remarks

To learn more about the role of death in life I warmly recommend you to study “The Worm at the Core” by Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg & Tom Pyszczynski which this article is based on. In this excellent, thought provoking, and easily read book you can also find more research examples of how reminders of mortality affects our thoughts and actions.

The authors base their idea about the centrality of death on the late cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker whose book “The Denial of Death” you can find an introduction to here on this website.

For more blog posts on the terror of death see, for instance, my introduction to Irvin Yalom on the terror of death, Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard or existential psychotherapist and KZ Camp survivor Viktor Frankl on meaning in the face of death.

The Skeleton-Man Show Death: The High Price of Living

In my new show Death: The High Price of Living I introduce the audience to the existential tradition. You can find more information about the show here that is specifically targeted educational institutions and companies, for instance, as a fun and engaging event at the yearly company art club assembly.

For BOOKING please contact info@skeleton-man.com