For BOOKING please contact info@skeleton-man.com

Introduction

A patient caught up in a highly self-destructive relationship stated: “I cannot decide what to do, I can’t bring myself to end the relationship, but I pray that I could catch him in bed with another woman so that I would be able to leave him.”

So speaks the american psychotherapist Irvin Yalom in his book “Existential Psychotherapy” from 1980. Irvin Yalom continues:

Ordinarily we think of freedom as an unequivocally positive concept. Throughout recorded history has not the human being yearned and striven for freedom? Yet freedom viewed from the perspective of ultimate ground is riveted to dread. In its existential sense “freedom” refers to the absence of external structure. Contrary to everyday experience, the human being does not enter (and leave) a well-structured universe that has an inherent design. Rather, the individual is entirely responsible for – that is, is the author of – his or her own world, life design, choices, and actions. “Freedom” in this sense has a terrifying implication: it means that beneath us there is no ground – nothing, a void, an abyss.

Irvin Yalom (b. 1931)

Responsibility assumption

When considering freedom Irvin Yalom makes the distinction between responsibility assumption and willing.

According to Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) to be responsible is to be “the uncontested author of an event or a thing.” To be aware of responsibility is to be aware of creating one’s own self, destiny, life predicament, feelings and, if such be the case, one’s own suffering.

Hence, the universe is contingent; everything that is could have been created differently. Sartre’s view of freedom is far-reaching: the human being is not only free but is doomed to freedom. Note that Sartre’s point is not moral: he does not say that one should be doing something different, but he says that what one does do is his or her responsibility. As Yalom warns us this is a deeply frightening insight. Consider its implication:

Nothing in the world has significance except by virtue of one’s own creation. There are no rules, no ethical system, no values; there is no external referent whatsoever; there is no grand design in the universe. In Sartre’s view, the individual alone is the creator (this is what he means by “man is the being whose project is to be god).” To experience existence in this manner is a dizzying sensation … [where] the very ground beneath one seems to open up.

To protect oneself from responsibility awareness the individual may turn to a number of psychic defenses:

Compulsivity: A common dynamic defense against responsibility awareness it the creation of a psychic world in which one does not experience freedom but exists under the sway of some irresistible ego-alien (“not-me”) force.

Displacement of responsibility: Another common way to avoid personal responsibility is by displacing it to another (vis-a-vis the example in the opening lines of this blog post).

Denial of responsibility: innocent victim: An individual may deny responsibility by experiencing him- or herself as an innocent victim of events that they themselves have (unwittingly) set in motion.

Denial of responsibility or losing control: The claim that one was temporarily “out of one’s mind.”

Avoidance of autonomous behavior: One can be baffled by what man is willing to accept and what opportunities he or she is ready to waste to avoid responsibility assumption even when man is fully aware what he or she needs to do. But accepting one’s “faith” or circumstances without any resistance can be less terror producing than to assume responsibility.

Of course, one can argue that any choice must be seen in its context. Are you drowning in a deep swimming pool your options are drastically curtailed. But as Irvin Yalom emphasize:

… even immersed to the neck, a human being has the freedom to choose how to feel about the situation, what attitudes to adopt, whether to be courageous, stoic, fatalistic, cunning, or panicked … This is no minor quibble. Even though the image of a drowning man’s possessing freedom may appear ludicrous, the principle behind the image is of great significance. One’s attitude toward one’s situation is the very crux of being human, and conclusions about human nature based solely on measurable behavior are distortions of that nature. It cannot be denied that environment, genetics, or chance plays a role in one’s life. The limiting circumstances are obvious: Sartre speaks of a “coefficient of adversity.” All of us face natural adversities that influence our lives – physical handicaps, inadequate education, poor health, and so forth – but that does not mean that we have no responsibility (or choice) in the situation. We are still responsible for what we make out of our handicaps; for our attitudes toward them; for the bitterness, anger, or depression that act synergistically with the original “coefficient of adversity” to ensure that a handicap will defeat the individual.

To raise awareness of responsibility, however, is also to invite existential guilt. The discrepancy between what one is and what one could be generates a flood of self-contempt with which the individual must cope throughout life. When the “call of conscience” is heard (that is, the call that brings one back to facing one’s “authentic” mode of being), one is always “guilty” – and guilty to the extent that one has failed to fulfill authentic possibility. The psychoanalyst Otto Rank (1884-1939) wrote that when we restrict ourselves from a too intensive or too quick living out, or living up, we feel ourselves guilty on account of the unused life, the unlived life in us.

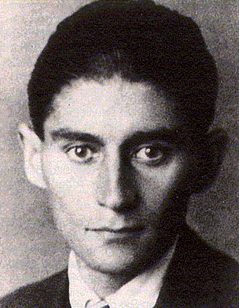

Franz Kafka’s “The Trial”

No one has described existential guilt better than Franz Kafka. The Trial begins, “Someone must have maligned Joseph K., for without having done anything wrong, he was arrested one fine morning.” At first it appears that Joseph K. is confronted with an authoritarian and bureaucratic system but as the reader gradually realises, Joseph K. is confronted with an internal court residing in his private depths. And in this respect he is guilty; guilty in his unlived and lonely life.

Hoping to circumvent the court Joseph K. asks a priest if he can find “a mode of living completely outside the jurisdiction of the court” (that is, outside his own conscience). The priest replies with the searing tale of a man and a doorkeeper. A man from the country begs admittance to the law. A doorkeeper in front of one of the innumerable doors greets him and announces that he may not be admitted at the moment. When the man attempts to peer through the entrance, the doorkeeper warns him: “Try to get in without my permission. But note that I am powerful. From hall to hall, keepers stand at every door, one more powerful than the other and the sight of the third man is already more than even I can stand.”

The supplicant decides that he had better wait until he gets permission to enter. He waits for days, for weeks, for years. He waits outside that door for his entire life. He ages; his vision dims; and as he lies dying, he poses one last question to the doorkeeper, a question he had never asked before: “Everyone strives to attain the law. How does it come about then, that in all these years no one has come seeking admittance but me?” The doorkeeper bellows in the man’s ear (for his hearing, too, is fading): “No one but you could gain admission through this door, since this door was intended for you. I am now going to shut it.”

The parable is moving but how is one to find one’s potential? How does one recognize when one meets it? How does one know when one has lost one’s way? Irvin Yalom has no doubt:

Heidegger, Paul Tillich, Abraham Maslow, and Rollo May would all answer in unison: “Through guilt! Through anxiety! Through the call of conscience!” There is general consensus among them that existential guilt is a positive constructive force, a guide calling oneself back to oneself.

Willing

As Irvin Yalom emphasizes awareness of responsibility in itself is not synonomous with change. With awareness of responsibility one merely enters the vestibule of change but the passage from awareness to action remains. And this passage may be insurmountable for the patient.

Wishing requires feeling. If one’s wishes are based on something other than feelings – for example, on rational deliberation or moral imperatives – then they are no longer wishes but “shoulds” or “oughts,” and one is blocked from communicating with one’s real self.

Once an individual fully experiences wish, he or she is faced with decision or choice. Decision is the bridge between wishing and action. The philosopher and psychologist William James (1842-1910) described five types of decision:

The reasonable decision where we consider the arguments for and against a given coure and settle on one alternative. We make this decision with a perfect sense of being free.

The willful decision: A willful and strenuous decision involving a sense of “inward effort.” This is a rare decision; the great majority of human decisions are made without effort.

The drifting decision: In this type there seems to be no paramount reason for either course of action and we make the decision by letting ourselves drift in a direction seemingly accidentally determined from without.

The impulsive decision: We feel unable to decide and the determination seems as accidental as the third type But it comes from within. We act automatically and often impulsively.

Decision based on a change of perspective: This decision often occurs suddenly and as a consequence of some important outer experience or inward change (for example, grief or fear) which results in an important change in perspective or a “change in heart.”

But decisions are very expensive; they cost you everything else. The psychoanalyst Allen Wheelis (1915-2007) stated the issue beautifully:

Some persons can proceed untroubled by proceeding blindly, believing they have traveled the main highway and that all intersections have been with byways. But to proceed with awareness and imagination is to be affected by the memory of crossroads which one will never encounter again. Some persons sit at the crossroad, taking neither path because they cannot take both, cherishing the illusion that if they sit there long enough the two ways will resolve themselves into one and hence both be possible. A large part of maturity and courage is the ability to make such renunciations, and a large part of wisdom is the ability to find ways which will enable one to renounce as little as possible.

Irvin Yalom adds:

Decision, especially an irreversible decision, is a boundary situation in the same way that awareness of “my death” is a boundary situation. Both act as a catalyst to shift one from the everyday attitude to the “ontological” attitude – that is, to a mode of being in which one is mindful of being. Although, as we learn from Heidegger, such a catalyst and such a shift are ultimately for the good and prerequisites for authentic existence, they also call forth anxiety.

And if one is not prepared, one develops modes of repressing decision just as one represses death. Such repressing can take various forms.

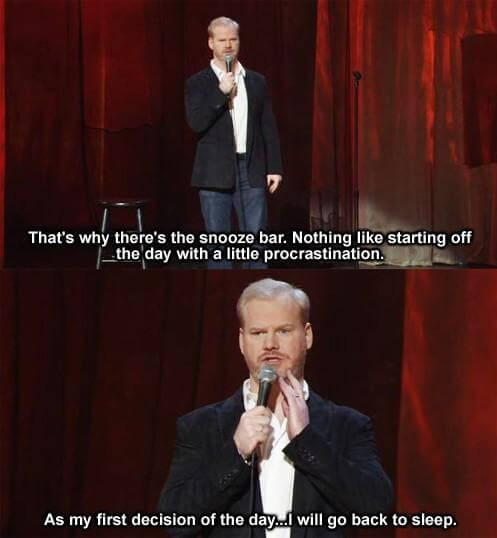

Procrastination: The most obvious method of avoiding a decision is procrastination, but one can also suppress a decision much more subtly.

Avoidance of renunciation: It makes it easier to relinquish one possibility if one convinces oneself that one does not really need the alternative possibility.

Devaluation of the unchosen alternative: Magnifying, at an unconscious level, slight differences between two fairly equal options so that the decision between them is both obvious and painless.

Delegating the decision to someone: A way to avoid the burden of decision and the ensuing awareness of our fundamental isolation is to persuade another to make the decision for one. Erich Fromm (1900-1980) repeatedly emphasized that the human being have always had a highly ambivalent attitude toward freedom. Though humans fight fiercely for freedom, they leap at the opportunity to surrender it to a totalitarian regime that promises to remove the burden of freedom and decision from them. Moreover, if someone else makes the decision, the individual will not be committed to making the decision work.

Delegating the decision to something: This can take several forms, for instance, succumbing to religious or legal dogma and rules. A third version is described by Luke Rhinehart in his novel The Dice Man, in which the protagonist leaves everything to the toss of a dice.

These defenses may soften confrontation with freedom and personal responsibility, but the price is impaired self-esteem and self-contempt. If one is to love oneself, one must behave in ways that one can admire. Only when one realize that one cannot not decide and if one fully accepts the ubiquity of one’s decision, then one confronts one’s existential situation in authentic fashion.

It is extraordinarily difficult to absolve guilt for the past in the presence of ongoing guilt-provoking behavior. One must learn first to forgive oneself for the present and the future. So long as one continues to operate toward the self in the present in the same way that one has acted in the past, then one cannot forgive oneself for the past. But when working with the past, it is important that the individual does not assume disproportionate responsibility. One important concept is the categorical imperative for responsibility; what is true for one regarding responsibility is true for all. Many individuals assume excessive responsibility and guilt for others’ actions and feelings. Though the person may truly have transgressed against another, there’s also a realm of responsibility of the other who allowed him- or herself to be hurt, scorned, or otherwise mistreated.

And again:

The best way – perhaps the only way – of dealing with guilt – guilt from violation either of another or of oneself – is through atonement. One cannot will backward. One can atone for the past only by altering the future.

With those last words of advise from Irvin Yalom we conclude this introduction to freedom as an ultimate concern. If this post has warmed you to the existential tradition you can find more blog posts on death, existential isolation and meaninglessness here.

The Skeleton-Man Show Death: The High Price of Living

In my new show Death: The High Price of Living the audience is introduced to the existential tradition. You can find more information about the show here that is specifically targeted educational institutions and companies, for instance, as a fun and engaging event at the yearly company art club assembly.

For BOOKING please contact info@skeleton-man.com