For BOOKING please contact info@skeleton-man.com

The Denial of Death

In his 1974 Pulitzer Price winning book The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker, sets out on a grand project. To show how scientific insight and religious doctrine merges at the furthest and most fertile lands.

Becker (1924-1974) builds his case on one fundamental premise. That the (terror and) denial of death is the central theme in mans’ life. We may deny that it is so, says Becker, and claim that we are aware of death but that it does not frighten us. Becker, however, will not have this protest. It’s a purely intellectual dismissal, he says, but death cannot be grasped on any intellectual level.

Death is annihilation as if we never were. Of course, such a thought fills us with anxiety, says Becker. Not only that. It is the central anxiety in our life to which all else must answer. In fact, the terror and denial of death is a force so powerful that, in essence, everything we do in our lives is mounting an answer unto death.

But let’s first look at man and how the terror and denial of death plays out in the human being.

Man’s Paradoxical Nature; Half Animal, Half Symbolic

According to Ernest Becker the essence of man is his paradoxical nature; that he is half animal and half symbolic. What does this mean? It means that, on the one hand, man has a fallible body that will eventually decay and die. And he is regularly reminded of this in the most embarrassing of ways; by a hole located on his back and out of sight from which a stinking and repugnant substance regularly appears. If ever we think of ourselves as divine beings, surely, this is an aspect of our divinity we could do without!

Hence, on the one hand, man is an animal in the most achingly plain way. On the other hand, man is a creature that lives symbolically. In his mind he can go anywhere and everywhere. He can imagine himself at the dawn of creation or an infinite amount of years into the future. He can build edifices, businesses and family trees he believes will last forever and grant him symbolic immortality. And even if he himself may not be remembered he can be part of something larger than himself, a cause or a movement that will forever stand the test of time.

It is only if you let the full weight of this paradox sink down on your mind and feelings that you can realise what an impossible situation it is for man to be in.

On the one hand, man is able to imagine himself as a god; on the other hand, man is embarrassingly aware of his animal status and part of nature no more special than a grasshopper, mortal and finite. Gods with assholes, as Ernest Becker poetically names man. Symbolically we can do anything and everything but death ties us to this earth, this body and this lifetime and places a very clear road block to our endless aspirations and hopes. That is too much to hold in our minds. Too much knowledge to be aware of if we are to go through our daily lives with a modicum of ease.

Human Character as a Vital Lie

Thus, the terror of death is such an overwhelming and all-consuming thought that man has to produce a certain “madness” since he cannot accept nature as it is. And so each man develops his own personal madness in the form of character-traits through which he distills reality to fit his personal approach.

One may claim, therefore, that character traits are actually secret psychoses. What does this mean? It means that man creates a personal character, a front he shows the world that is dominated by certain traits. Why? Well, because the world is such a terrifying experience that will eventually do you in that man cannot confront it simply as it is. That would be too maddening. No, he has to fashion a certain way to deal with the world, a certain way he can hold it at length and so not be overwhelmed by its potential terrors. By creating his certain character man can tell himself he knows his ways of the world.

In other words, man lies to himself. Obviously, he will tell himself that he sees the world as it is but, in reality, he is only seeing what he wants to see and what his character-traits will allow him to see. His reality is actually an illusion that is cutting the world down to size. It may be an illusion that allows him to take in a big chunk of reality or an illusion that distorts reality to a very unhealthy and diminishing degree. But either way it is a distortion of reality he perceives.

The Enormous Challenge of Changing and the Need to Face our Fears

This view of man’s understanding of and relationship with the world has profound implications. First of all, it means that only when we face the terror of death that we carry around in our secret heart, only when we explode the innermost layer of our personality, do we get to the layer of what we might call our “authentic self”: what we really are without sham, without disguise, without defenses against fear.

This is why change is so hard! Real and lasting change requires that we first “die”, that is, face our innermost fear and the disguises in the form of character traits we have taken on to subdue this fear. Only then can we be reborn without the character-traits we want to do without. But a deep inner layer has to die for change to occur. In the words of Ernest Becker:

Psychological rebirth is a difficult and excruciatingly painful, all-or-nothing process that takes men of granite, men who were automatically powerful, secure in their drivenness, and it makes them tremble and cry.

And it is precisely so difficult because to face death, to see the world as it really is is devastating and terrifying. It achieves the very result that the person since childhood has painfully built his character over in order to avoid. It also makes routine, automatic, secure, self-confident activity impossible and places an enormous feeling of freedom and responsibility on ones shoulders on top of the death anxiety. That is a lot to face up to and so it may be a LOT more tempting not to face death, not to change and just keep doing what one has already been doing for years – and survived with doing, not the least!

Søren Kierkegaard

It is a testament to his genius that Søren Kierkegaard writing in the 1840s said as much himself.

Kierkegaard’s understanding of man’s character is that it is a structure built up to avoid the perception of the terror of death. What style does man use to function automatically and uncritically in the world, and how does this style cripple his true growth and freedom of action and choice?

The foundation stone for Kierkegaard’s view of man is The Myth of the Fall, the ejection of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. Man emerged from the instinctive thoughtless action of the lower animals and came to reflect on his condition. He was given a consciousness of his individuality and his part-divinity in creation, the beauty and uniqueness of his face and his name. But at the same time he was given the consciousness of the terror of the world and of his own death and decay. Thus, the fall into self-consciousness had one great penalty for man: it gave him dread, or anxiety.

The Inauthentic Man

Kierkegaard describes what we today call “inauthentic” men. They are “inauthentic” in that they do not belong to themselves and simply follow out the styles of automatic and uncritical living in which they were conditioned as children. For Kierkegaard “philistinism” was triviality, man lulled by the daily routines of his society, content with the satisfactions that it offers him: the car, the shopping center, the summer vacation.

For Kierkegaard a healthy person is a much more daring step. Since man takes part in divine creation but is himself a finite being, Kierkegaard says, a healthy person has to look for something far beyond man, something to be achieved, striven for, something that leads man beyond himself. The “healthy” person, the self-realised soul, the “real” man, for Kierkegaard, is the one who has transcended himself.

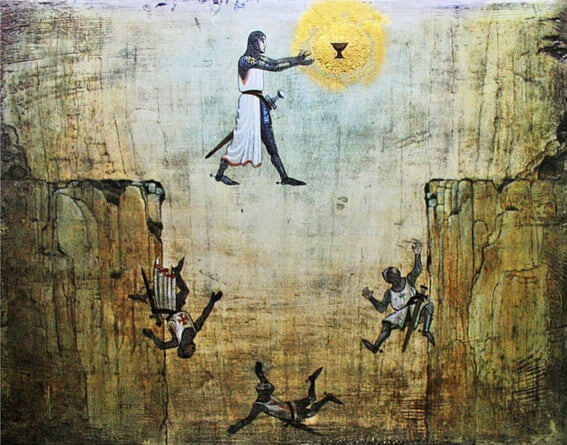

How does one transcend himself; How does he open himself to new possibility? By realising the truth of his situation, by dispelling the lie of his character and face up to the anxiety of the terror of existence. The finite self must be destroyed in order to see beyond to infinitude, to absolute transcendence, to the Ultimate Power of Creation which made finite creatures.

Once the person begins to look to his relationship to the Ultimate Power, to infinitude, and to refashion his links from those around him to that Ultimate Power, he opens up to himself the horizon of unlimited possibility, of real freedom. This is Kierkegaard’s message and the meaning of faith.

But standing on your own feet and look your fellow men straight in the eye is not an easy feat.

The Spell Cast by Persons

A winner of the Miss Maryland contest describes her first meeting with Frank Sinatra:

He was my date. I got a message, and I must have taken five aspirins to calm myself down. In the restaurant, I saw him from across the room, and I got such butterflies in my stomach and such a thing that went from head to toe. He had like a halo around his head of stars to me. He projected something I have never seen in my life … when I’m with him I’m in awe, and I don’t know why I can’t snap out of it … I can’t think. He’s so fascinating.

Why does man give his loyalty and obedience to this one or that one so blindly and willingly? One explanation is that we want to melt into the leaders aura. We transfer the feelings we had towards our parents as a child to the leader. We blow the leader up larger than life just as the child sees the parents. We become as dependent on him and draws protection and power from him just like a child merges his destiny with the parents.

In groups men simply become dependent children again, blindly following the inner voice of their parents, which now come to them under the hypnotic spell of the leader. They abandon their egos to his, identifies with his power, tries to function with him as an ideal. They do not fear danger any longer because they no longer feel alone with their smallness and helplessness, as they have the powers of the hero-leader with whom they are identified.

Safe Heroism and Merging with the Cosmos

The result is the practicing of a safe heroism where people will claim to believe in and fight for a bigger cause but with no courage to stand on their own feet for it. As part of the group the leader takes the real responsibility and everyone can see themselves as guiltless and temporary victims of the leader. When people try for heroics from the position of willing slavishness there is nothing to admire; it is all automatic, predictable, pathetic.

But however sad and pathetic, the desire to merge with a leader is also an expression of a deeper and beautiful desire to merge with ones surroundings. In Christianity it is the motive of Agape – the natural melding of created life in the “Creation-in-life” which transcends it.

When one merges with the self-transcending parents or social group one is, in some real sense, trying to live in some larger expansiveness of meaning. Becker stresses that we miss an important complexity if we fail to understand this point when we consider group dynamics and the appeal of hypnotic leaders.

Natural Guilt

According to Otto Rank (1884-1939) man is born with a natural guilt, ie. a guilt that is deeply ingrained in every person from the moment we exit the womb. On the one hand, man has a need to stick out. On the other hand, he feels guilty for wanting to stick out and then more guilt when he does stick out. It’s a feeling of “unworthiness” that man has – and for good reasons. Compared to the rest of nature man is not a very satisfactory creation. Who is he to suggest he has the right to stand out?!

This makes standing out a very daring venture that takes a strength and courage the average man doesn’t have. To stick out exposes the person to the sense of being completely crushed and annihilated because he has to carry so much unto himself.

The Creative Type and Natural Guilt

This need to stick out is the defining character-trait of the artist type, or the creative type generally. The key to the creative type is that he is separated out of the common pool of shared meanings. There is something in his life experience that makes him take in the world, as a problem. As a result he has to make personal sense out of it. Existence becomes a problem that needs an ideal and personal answer. The work of art, then, is the ideal answer of the creative type to the problem of existence as he takes it in.

But, Becker notes, if the artist is to avoid overwhelming guilt he cannot base the merits of his art on his own value. Only a God can do that. On the other hand, he cannot base it on his fellow men since he is trying to create something new that eclipses them. Hence, the artist’s gift must always be a work of art to creation itself, to God. This, then, is also the only way for the artist to work around natural guilt.

Psychoanalysis as the New Religion and the Therapist as the New Messiah

What characterizes modern life, Becker says, is the disappearance of convincing dramas. Man cannot find his heroism in everyday life any more, as men did in traditional societies just by doing their daily duty of raising children, working, and worshipping. Instead, he ends up needing revolutions and wars and “continuing” revolutions. That is the price modern man pays for the eclipse of the sacred dimension.

Otto Rank also saw that modern man was left to his own resources, and he called him aptly “psychological man.” Psychological because he became isolated from protective collective ideologies and had to justify himself from within. But also psychological because modern thought itself evolved that way when it developed out of religions.

The Problem with Psychology

The problem with putting this much weight on psychology is that it narrows the cause for personal unhappiness down to the person himself, and then he is stuck with himself. But all the analysis in the world won’t allow the person to find out who he is and why he is here on earth, why he has to die, and how he can make his life a heroic triumph.

The challenge of faith is that it asks of man that he expands himself trustingly into the nonlogical, into the truly fantastic. But modern man finds this spiritual expansion most difficult, precisely because he is constricted into himself and has nothing to lean on, no collective drama that makes fantasy seem real because it is lived and shared.

But since man still needs a “thou” to whom to turn for spiritual and moral dependence, and since God is not in fashion, the therapist has had to replace him. The therapist is the new God who must replace the old collective ideologies of redemption as reflected in the popular Hollywood myth.

Mental Illness as an Extreme Version of Common Character-traits

For the depressed person self-accusations of worthlessness are not only a reflection of guilt over – very real! – unlived life but also a language for making sense out of one’s situation. The depressed person uses guilt to hold onto his world view and to keep his situation unchanged. Otherwise he would have to analyse it or be able to move out of it and transcend it. Better to take on guilt then, even exaggerate it to compensate for the lack of action.

This discovery is of utmost importance. We take on guilt freely and willingly, even exaggerate it to convince ourselves that we are decent people even if we are flawed. Because, at least, we feel guilty about our flaws! Hence, by being remorseful and showing guilt, we give ourselves just enough excuse not to change. Yes, we would be “better people” if we changed this or that but this is the second best solution; We don’t change but we do feel guilty about it! This approach may have the consequence that we have to tell ourselves (and possibly the world) that we are useless, no good and hopeless. But at least we don’t have to change! We don’t have to question our character-traits and, thus, look death in the eye.

The Schizophrenic – All Symbolic and No Body

If depression is based on too much restriction, too much holding ourselves down, schizophrenia represents the other extreme solution: too much possibility. The schizophrenic reflects on himself, and comes to understand that his animal body is a menace to himself and lives completely in the symbolic realm. Terror becomes unabsorbable by anything neural or fleshy and your symbolic awareness floats at maximum intensity all by itself. For the schizophrenic the body has completely “happened” to him. The only thing intimate about it is that it is a direct channel of vulnerability.

In this way the schizophrenic is very much like the creative type but if the schizophrenic has no talent he is simply totally crippled by life-and-death fears whereas the creative and talented, equally schizophrenic may channel his response in the work of genius. This is also the explanation why the line between the madhouse and the celebrated artist and creative type is sometimes very thin.

A Merger of Psychology & Religion

Kierkegaard had his own formula for what it means to be a man when he described “the knight of faith.” This figure is the man who lives in faith, who has given over the meaning of life to his Creator, and who lives centered on the energies of his Maker. He accepts whatever happens in this visible dimension without complaint, lives his life as a duty, faces his death without a qualm. No pettiness is so petty that it threatens his meanings: no task is too frightening to be beyond his courage. He is fully in the world on its terms and wholly beyond the world in his trust in the invisible dimension.

The great strength of such an ideal is that it allows one to be open, generous, courageous, to touch others’ lives and enrich them and open them in turn. As the knight of faith has no fear-of-life-and-death trip to lay onto others, he does not coerce or manipulate them. The knight of faith, then, represents what we might call an ideal of mental health, the continuing openness of life out of the death throes of dread.

Put in these abstract terms the ideal of the knight of faith is surely one of the most beautiful and challenging ideals ever put forth by man. It is contained in most religions in one form or another, although no one has described it at length with such talent as Kierkegaard. Like all ideals it is a creative illusion, meant to lead men on, and leading men on is not the easiest thing.

Do We Choose God or Science?

Still, man can oscillate between religious creatureliness and scientific creatureliness. But how to choose one over the other? How does one lean on God and give over everything to Him and still stand on his own feet as a passionate human being?

Well, we have to remember that fear of death is not the only motive of life. Heroic transcendence, victory over evil for mankind as a whole, for unborn generations, consecration of one’s existence to higher meanings – these motives are just as vital and they are what give the human animal his nobility even in the face of his animal fears. Hedonism is not heroism for most men but modern men do not realise this and so sell their souls to consumer capitalism or replace their souls with psychology. Psychotherapy is such a growing vogue today because people want to know why they are unhappy in hedonism and look for the faults within themselves.

This is not to say psychotherapy cannot give great gifts to tortured and overwhelmed people. It can allow people to affirm themselves, to smash idols that constrict the self-esteem, to lift the load of neurotic guilt. But often psychotherapy seems to promise the moon: a more constant joy, delight, celebration of life, perfect love, and perfect freedom. It seems to promise that these things are easy to come by, once self-knowledge is achieved, that they are things that should and could characterize one’s whole waking awareness. But “Psychology as self-knowledge is self-deception,” Otto Rank said, because it does not give what men want, which is immortality. Nothing could be plainer.

The Value of Myth and Creative Illusion

Myths and creative illusion may be just that, myths and illusion, but that does not mean that they in themselves are bad. Some myths are vegetative and generate real conceptual power, real apprehension of a dim truth we miss by sharp, analytic reason. But if we are going to have a myth of a New Being, Becker stresses, then we have to use this myth as a call to the highest and most difficult effort – not simple consumerism or psychology. A creative myth is not simply a relapse into comfortable illusion; it has to be as bold as possible in order to be truly generative.

There is no nonsense here. For man to have the “courage to be” himself, his daily life becomes truly a duty of cosmic proportions, and his courage to face the anxiety of meaninglessness becomes a true cosmic heroism. No longer does one do as God wills, set over against some imaginary figure in heaven. Rather, in one’s own person he tries to achieve what the creative powers of emergent Being have themselves so far achieved with lower forms of life: the overcoming of that which would negate life.

In the mysterious way in which life is given to us in evolution on this planet, it pushes in the direction of its own expansion. We don’t understand it simply because we don’t know the purpose of creation.

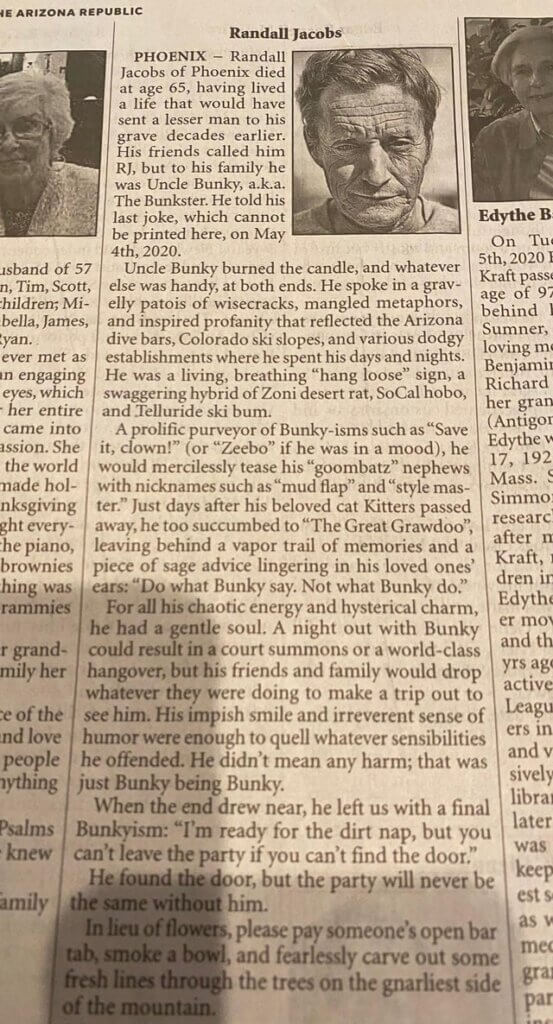

In conclusion, Ernest Becker finishes, a project as grand as the scientific-mythical construction of victory over human limitation is not something that can be programmed by science. Who knows what form the forward momentum of life will take in the time ahead or what use it will make of our anguished searching. The most that any one of us can seem to do is to fashion something – an object or ourselves – and to drop it into the confusion, make an offering of it, so to speak, to the life force.

With those words we conclude this introduction to Ernest Becker and The Denial of Death. If anything, I hope this introduction will send the reader directly to his book. I found parts of it somewhat challenging but when it finally opened up I found it to be most inspiring.

For more articles on existentialism also see my other blog posts on the terror of death, personal freedom, existential isolation and meaninglessness.

The Skeleton-Man Show Death: The High Price of Living

In my new show Death: The High Price of Living I introduce the audience to the existential tradition. You can find more information about the show here that is specifically targeted educational institutions and companies, for instance, as a fun and engaging event at the yearly company art club assembly.

For BOOKING please contact info@skeleton-man.com