For BOOKING please contact info@skeleton-man.com

Foreword

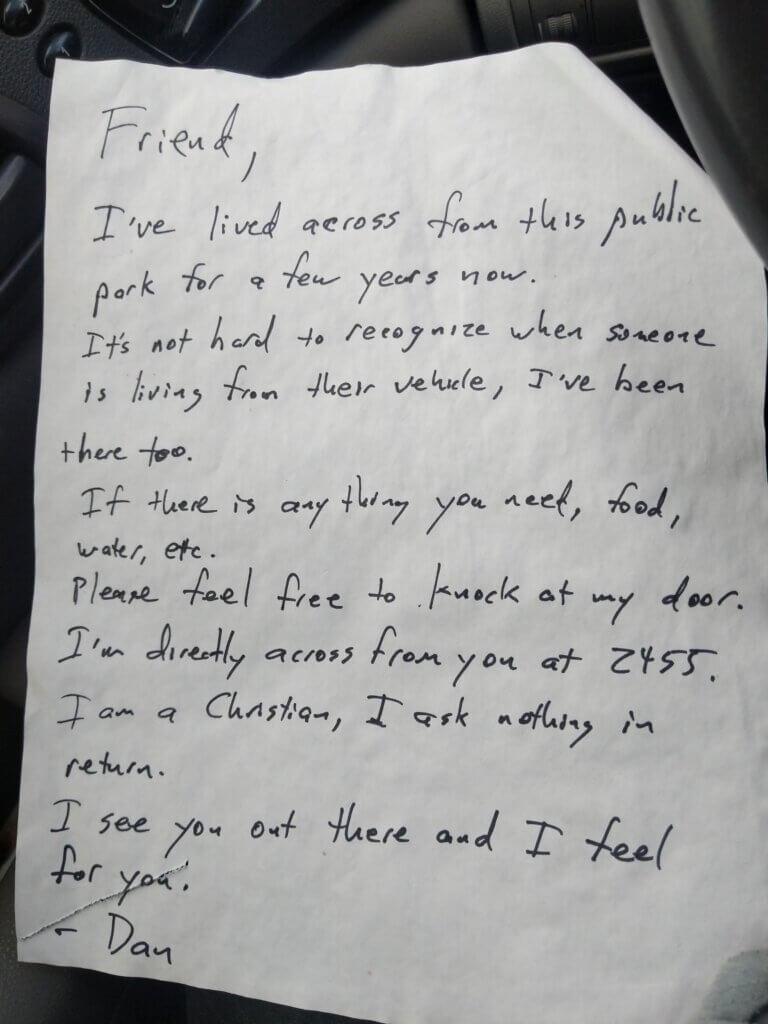

Søren Kierkegaard lived from 1813-1855. He was a Christian theologian and philosopher and is often referred to as the father of the existential movement. His writings often dwell on the dark sides of life but the keyword for Kierkegaard is joy. He worshipped everyday life even though he was never able to enjoy it himself. He did, however, spend his entire authorship identifying the conditions for living an authentic and joyful life in accordance with oneself and God.

In this blog post and in the video below you will find a brief introduction to his key points. Hopefully this will give you an idea of his mission and an interest in learning more. Before diving into Kierkegaard’s own works I do recommend, however, first to go through an introductory text that in more details explains his philosophy. It is multi-facetted and without any preparation he is difficult to get a grip on. For Danish readers the books “Kierkegaards univers” by Johannes Sløk and “Kirkegaards filosofi” by Peter Thielst offers splendid introductions.

Once you get to appreciate his key insights he has lots to offer. See for instance how Ernest Becker uses Kirkegaard’s insights in his 1974 Pulitzer Prize willing book “The Denial of Death“ that further expands on Kierkegaard’s work.

When Reading Kierkegaard

Kierkegaard makes a distinction between objective knowledge and subjective knowledge. Objective knowledge is knowledge about the world as it is, ie. physical observations or logical/mathematical truths. A distinctive feature of objective knowledge is that it is governed by consensus. Subjective knowledge, on the other hand, is knowledge that can only be ascertained on an individual basis and that has to be realised deeply within for it to be true. Questions concerning man’s existence all fall under this category. This makes reading Kierkegaard challenging because you cannot simply learn and understand his points of view by being able to repeat them. You have to experience them deeply within for them to be true.

For instance, Kierkegaard speaks of man as a unity of man and society. He also says that to become a real (authentic) person one must choose oneself as one is, and choose society as it is, because man and society are both given by God and, hence, absolutely and unquestionably good.

It can be all well and good to learn this by heart and repeat as lingo but what does it mean? It means that you must be able to love yourself exactly as you are, including any and all aspects of you that you would rather be without because those aspects are every bit as much you as the aspects you are proud off. Conversely, you need to be able to receive whatever your surroundings “sends” your way because also this is good. No matter if this is the aching and fulfilled first love or a car crash that handicaps you and kills your entire family. Yes, Kierkegaard is this unforgiving. In other words, you must learn to find the beauty in everyday repetition no matter the conundrum, the burden, the hardship of it and love the marvel of the wonder that is life.

This is not always easy! But if you want to understand Kierkegaard’s point you have to be willing to try since he is advocating a subjective truth that will only hold truth for you once you have grasped it.

Kierkegaards Background

Søren Kierkegaard was born in 1813 and grew up in Copenhagen in a wealthy home marked by guilt, pietism and a melancholic and dominating father. Søren was the youngest of seven siblings born when his father was 56 and his mother 45. All Soren’s siblings except for one brother died relatively young and Soren himself was convinced he wouldn’t live past his 33rd birthday (which his father also believed and regularly reminded him!). We don’t know much about Soren’s mother. Soren never mentions her in his works, but she was a woman of modest education and in all likelihood a good mother for the children. We know that Soren was very affected when she died in 1834. In any case, the home was a good breeding ground for deep thoughts – especially if one was already prone for depression.

Kierkegaard, however, is not a dark pietist or forsaker of life. Kierkegaard advocated the enjoyment of life in his personal doings as well as a matter of philosophical principle. The true goal for all endeavours, he said, is to be able to live in a deep, undisturbed enjoyment, where one is able to take life in to the fullest, from moment to moment, and get the most out of it.

Pseudonymous Writers

His writings are not easy to grasp. This is partly because a lot of Kierkegaard’s books were written under pseudonym. Kierkegaard used this method because he believed that truths, that pertain to man’s existence, has to be comprehended in one’s own mind and in one’s own existence for them to be true. Otherwise, they are just lingo. Therefore, the reader should not be influenced by whatever authority wrote the book but make up his own mind. Moreover, each writer that Kierkegaard would invent had his own point of view and so Kierkegaard’s many writers ends up analyzing the different themes and subjects from a plentitude of angles, even commenting on each others work. The reader can then himself decide which writer he agrees with the most.

Regine Olsen

Kierkegaard’s life was not marked by many dramatic events but the disastrous engagement with the 17 years old Regine Olsen is central in the understanding of Kierkegaard. The 10 years older Kierkegaard had expended all his charms to force an engagement through only to instantly realise that he was incapable of going through with the engagement. When Regine would not call off the engagement he behaved in such brute manner that she was forced to call it off. It was the scandal of the town and Kierkegaard practically fled to Berlin.

He never forgave himself the affair that plays an integral part in his works. But his journey to Berlin also became the starting point of his authorship that made him one of the greatest philosophers ever and one of the few that really broke new grounds.

The Lost Reality of the Philistines

It is a condition for man, says Kierkegaard, that while he is born as a human being that only means that he is born with the possibility of becoming a human being. Man’s immediately given reality is a lost reality and one only becomes a human being when one has identified oneself with the specific abilities and environmental circumstances one is beforehand and have made them one’s own.

If a person does not undertake the proces of realization, the self will not materialize; man will not become identical with his self. Instead man will loose himself into all that he immediately is and become a mindless cog in a machinery, destined to function in the manner the machinery forces it to.

Kierkegaard calls this person the philistine. The main characteristic of the philistine is that he is completely and fully – yet totally ignorant about it – a product of what his surroundings and culture will make of a person with his talents and dispositions.

Despair

The philistine, therefore, lives in despair, says Kierkegaard, since his life is not dependent on himself, but on the conditions. In Kierkegaard’s words the philistine always has the condition outside himself. Consider the sportsman or businessman that base their entire self understanding on their profession. If the sportsman suffers from a fatal injury or the businessman goes helplessly bankrupt, they despair. It is their lives they have lost. Living dependent on conditions that are outside of your control is living in despair.

A philistine is always a philistine without knowing he is a philistine, but what happens when he discovers his self deceit? Well, now he really despairs because now he no longer despairs over something specific, but because he discovers that, in essence, he has always been living in despair.

The Aesthetic

If the philistine cannot shake off his unsettling mood he becomes an aesthetic. This is a difficult concept but it may loosely be defined as “uninterested enjoyment”, that is, a state of mind where one takes pleasure without being soothed to expend any energy.

Aesthetics on principle never engage themselves. They are intentionally uninterested and relates to and view life as a farce, a grotesque and absurd theatrical play with no coherence or meaning. For the aesthetic it is logically impossible to make a decision since nothing matters and everything leads to the same. That is why one of Kierkegaard’s aesthetics in his debut novel Either/Or can say: Marry and you will regret it; do not marry and you will regret it; either you marry or you don’t marry you will regret both. Hang yourself and you will regret it; do not hang yourself and you will regret; whether you hang yourself or you don’t hang yourself you will regret both. Ad infinitum.

The only attitude that can match this state of affairs is the ironic one. But an ironic stance towards the philistine reality will not relinquish the aesthetic. An ironic attitude only means that, like a planet must orbit the sun, so the ironic will remain interdependent on the world he wishes to distance himself from.

Hence, the aesthetic is a tragic figure. He has, however, discovered one aspect of life that the philistine lacks: Passion. Passion is the deepest inner bearing in man’s life. Without passion one has the philistine world where all purposes and efforts serves as a cover to hide the underlying emptiness. The task for the human being is, in reality, to give in to passion and let passion rule. Only, the aesthetic cannot get a firm grip on his passion.

The Ethical and the Ethical Demand

In order to make the transition from the aesthetic to the ethical one must not live in despair; one must choose despair. This can sound counterintuitive. Say, if one is a bit lazy and wants to be more energetic ought one not to choose oneself as more energetic? If I just choose myself as I am, lazy, what good can come of that?

If you think this way then you have not fathomed what “to choose” means. To choose is to will. And when one chooses oneself, when one wills oneself, exactly as one is, it has consequences.

To Choose Oneself

Let’s consider an alcoholic. He is in deep despair and would more than anything like to choose himself as one that is not an alcoholic. But this has the consequence that he can only become identical with himself when he has overcome his alcoholism. Hence, his struggle against his alcoholism will be desperate and in despair and if he fails he will break completely down since it is his very self he has lost.

If, on the other hand, he chooses himself as an alcoholic everything looks different. He is now himself, identical with himself also when he is drunk. He can still try to quit his alcoholism but he no longer tries so desperately and if he relapses he won’t despair because he is reconciled with himself also in his misery.

To exist in this manner, reconciled with oneself because one has fully and completely said yes to oneself, that is in Kierkegaard’s view the road to a sound mental health but it is more than that. It is fulfilment of the ethical demand and the only manner in which responsibility can come about, but then as a full responsibility. A responsibility that cannot be relativized or limited, cannot be made dependent on heritage, environment or social circumstances etc. When man chooses himself, he becomes the cause of himself.

The Cause of Yourself

If you are an alcoholic it is your responsibility; you have willed it and chosen it. It may be that you have had a tough upbringing but when you choose to will yourself you also have the full responsibility for what you want to do and no matter what you choose to do you can do so without desperation or despair. Because in choosing also lies reconciliation and reassurance. By willing yourself you unconditionally forgive yourself and, thus, if your attempt fails it doesn’t matter (at least with respect to how you can and should feel about yourself).

NOTE that in the same manner man honestly must choose himself, so he must choose society, ie. his surroundings as a whole, as it actually is – with all the flaws it may have. This is absolutely essential. In Kierkegaard’s view man is a unity of man and society and to attain that unity man must choose (and receive) himself in the same manner that man chooses (and receives) society as it is. Or in other words: Man must choose himself, as he is, where he is. When man does this he opens himself to an authentic life in unity with his fellow human beings. Moreover, everyday life becomes a joyful duty when one lives up to ones’ duty and does all the things one really does want to do: Marry and start a family, have a job, friends and a function in society.

The Ethical Duty

Duty sounds boring (and Kierkegaard deliberately makes an ethical existence sound as boring as possible) but let’s look at the concept of duty using love as an example. The aesthetic loves, but he loves for his own sake. He loves the people in his life because of what they do to or for him. The ethical loves the people in his life for their own sake. It is an alteration of love. For the ethical the idea of love is not what he can have from the beloved but what he can give the beloved. This video on Fish Love puts it well.

It is important to emphasize that this understanding of love takes nothing away of the beauty in love. On the contrary, ethical love is always young and new because it does not depend on a feeling but on an attitude. And feelings can be deceitful but the attitude is firm.

Behind it all lies the fundamental concept: Passion. When man passionately wills himself he also becomes a social self. In love man does not love himself, but the other, which in reality is the only true way of loving oneself. One realises oneself by becoming part of the community. Only then has one realised oneself as the unity of individual and society.

But existence can become even richer, says Kierkegaard. To understand how we must first understand his analysis of ’the repetition’.

Repetition and the Establishment of the Religious

The ethical lifeform glorifies the monotonous repetition, the everyday treadmill of life, but what happens when life is not a treadmill? What to do if your world is shaken to the core in the most dramatic of ways, your entire family killed in a car accident? Is it still possible to ‘repeat’, ie. take up life again no matter the circumstances?

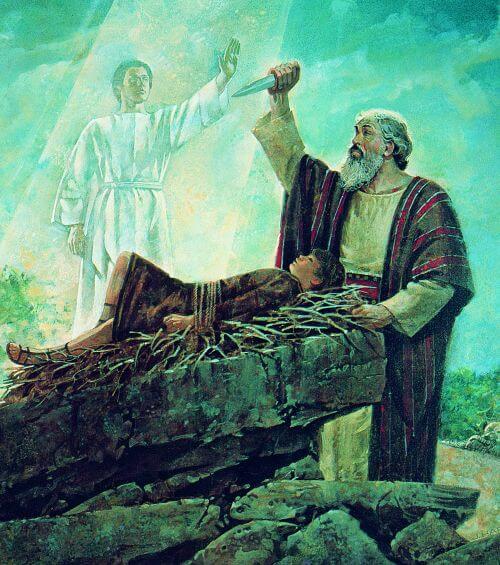

To consider this situation Kierkegaard analyses the story of Abraham that is commanded by God in the Book of Genesis to sacrifice his son Isaac. For Abraham the command to sacrifice Isaac amounts to a break with everything that is ethical, the ‘common’ or ‘normal’. In reality, it is not just Isaac he kills; he kills all existence, all meaning, rationality and coherence in the world when he kills Isaac. If such an act is permissible, there is no purpose left in the world. It is the ethical as a whole that is killed. Abraham’s world can therefore only be ‘saved’ if it is possible to establish what Kierkegaard calls a ‘teleological suspension of the ethical’.

But what purpose could possibly suspend the ethical? A religious purpose can suspend the ethical! God can suspend the ethical! But this raises a new question: Is it possible to live an authentic life in unity with the ethically ordered society if God and the religious as a superior power sets an absolute demand that can suspend the ethical?

Yes, it is possible. The keyword is faith. Faith entails that Abraham first ‘resigns indefinitely’. When God demands Isaac of him he bows to the demand of God without hesitation. He gives up Isaac and resigns indefinitely on him.

But right after resigning indefinitely Abraham performs the opposite ‘movement’ He believes and in his faith Abraham receives not only Isaac back but the entire meaning of existence.

But … believes in what? Has faith in what? Receives Isaac back how? Kierkegaard’s pseudonymous writer, Johannes de silentio, that is the author of the analysis, admits that he doesn’t understand it but rationally he can determine that faith is only faith when it is ‘faith by virtue of the absurd’. Faith lies beyond rationality and common sense. Faith is what ‘takes over’ when common sense has reached its limits. Otherwise it would not be faith. Faith means that Abraham receives Isaac back even after having resigned on him indefinitely.

not without doubt

The Knight of Faith

Hence, Abraham represents the ‘Knight of Faith’. This faith goes far beyond the ethical faith in God that, basically, is nothing but the precondition that man can choose himself and attain personal responsibility. The God, Abraham believes in, lies outside or above the ethical system, beyond the limits of common sense where there is no rationality since the concept of God is the concept of the unfathomable. That’s why one can also say that the religious hope or the Christian hope is a hope, that lives, when there is no longer the possibility for any hope.

This differentiates ordinary human hopes and aspirations from the hope of faith. Everyday hopes can be expressed and base themselves on something, eg. I hope the girl likes me – she smiles at me. The religious hope is completely different. With the religious hope it is not possible to indicate with any modicum of certainty what it is exactly we hope for. We hope in God – and God is the unfathomable from whom one can expect the unexpectable like, say, a car crash or a saving angel (metaphorically speaking).

And with this the religious has been established as a new, higher, separate dimension in existence.

The Love Unto God and Guilt

In one of Kierkegaard’s ‘upbuilding discourses’ it is said that unto God we are always wrong. It can sound strange that such a remark would appear in an upbuilding discourse; is it not discouraging more than anything? The idea, however, is that one wants to be wrong unto God. That is the basis for the Christian joy and reassurance. God cannot be explained or defended, needs no explanations or apologia and the Christian believer is reconciled with himself and his life in his infinite love unto God.

Infinite love unto God. Why, that is passion! What man is in his innermost being. The aesthetic’s passion is basically self love; the ethical’s passion is his fellow beings; but in the religious realm human passion has found its’ true and final target, the religious love unto God. And remember that God is not a person that one can go about loving; God is the unfathomable, the eternal, the unforeseeable; that, which cannot be, but which is.

The Religious Existence

Living religiously implies a duality. One must simultaneously live in a relationship with the world and in a relationship with God. Living religiously in relation to the world is realising ones’ being as the unity of individual/society.

The relationship with God is of a completely different nature and cannot, in fact, take any concrete form in the world. The religious is a new passion, faith by virtue of the absurd, the infinite love unto God as sheer possibility.

But how is this expressed then? As pure ‘sincerity’! It is incommensurable to the world, that is, it cannot take any form. And that is exactly what makes it so important in that it shows itself constantly and all the time in the way man relates to the world. That is the entire point. The content of ones existence hasn’t changed the slightest but one’s attitude towards that content is radically new and it is in this change the religious is expressed.

The question can also be considered as man’s problem with uniting eternity with temporality. If the eternal is absent, life becomes empty and meaningless, a thunder of nothingness. But eternal means the present moment, not the infinite passing of time. In relation to time the eternal is like time stopped, the always present, that is, a qualification of the given moment. But the given moment only becomes eternal when one in faith and unending passion receives it from God as the marvellous and unexpected, as the divine opportunity. Not only when one – as the ethic thinks – chooses it. There is continual creation in this line of thinking. That the next moment occurs is not the obvious, but the astounding. Religiously one lives in marvel over the gift of live that is given to us again and again.

The Religious Reception of Life

The important in all this is that man can now be fully and completely present in the ever fleeing now, in every single fleeing now. This presence, this simultaneity with oneself represents the succumbing of all, that otherwise is the curse of life: the restlessness, the concerns, the despair of what once was, the anxiety of what is to come, the relentless burden that one must carry ones’ own existence. In this way, the eternal’s union with temporality in the present moment is the creation of the eternal bliss right in the middle of life.

This is why Kierkegaard can say about joy: “What is joy or to be joyful? It is, truthfully, to be present to oneself, but to be truthfully present to oneself, that is this ‘today’, this to be today, truthfully, to be today.”

This does not mean that the religious will make all your worries and suffering disappear but it will offer you a new attitude towards lifes’ tribulations; Life, such as it is now, for me, has been given to me by God and therefore the verdict is that is is absolutely and unquestionably good.

Without the religious point of view all happenings in life are, essentially, mean, because we are lost to them, a plaything of their randomness, volatility and uncertainty. But by the religious, by the relationship between faith and God they all become good since they all flow from the ‘Father of Light’.

Note, however, that Kierkegaard is not saying that the religious person receives his life circumstances and conditions without protest or an impulse toward reform. Quite the contrary, the religious person can now protest and throw himself into action, but without desperation because no longer does everything depend on whether his actions are succesfull. Nothing rests finally on him any longer, but on God. For Kierkegaard it is, therefore, an important aspect of Christianity that it encourages action, in reality, revolutionary action with the aim of transforming the entire existence.

The Christian Paradox

In Kierkegaard’s view Christianity separates itself from all other religions by being a reality, a historic event of paradoxical nature, a divine intervention in history that has brought about completely new conditions for the life of man.

But Jesus’ life on earth also marks the passing from the religious, as such, to the specific Christian and sharpens the religious paradox.

Living religiously is the extreme of what a man can perform – but that also implies that man can actually live religiously. In Christianity it is presupposed that not even this feat is possible for man. Christianity then is the proclamation that God did what man cannot: Become a man.

This event changed everything. The dogma of the incarnation, that God became man, is in its’ essence Christianity. All other religions, all other types of philosophic views on understanding life are man’s feeble attempts to interpret existence. Christianity, however, is no such interpretation or reading. Christianity represents an event, an intervention from God following which man was provided with completely new conditions for living as a human being.

Christianity’s Political Influence

Kierkegaard was convinced that only via Christianity, of which the church was the authoritative body, was it possible for the individual citizens or ‘that individual’ to be fully present in the given society.

For this reason Kierkegaard was a bitter opponent of all religious tolerance. Tolerance could be all well and good in many circumstances but never with regards to religion. Christianity itself was pointedly indifferent; after all, it was the truth, God’s intervention in history and to honour an idea that anybody could become blissful in his own belief was blasphemy and detrimental to society.

Therefore, the clergy has a special responsibility. The priest should not pander to his congregation in order to become popular. Rather he should restore order. Kierkegaard’s claim rests on the fact that he was very wary of democracy. In a democratic society, Kierkegaard believed, that ‘that individual’ would disappear, that is, that all men before they can function properly in a community and become social, first needs to become themselves. Kierkegaard was convinced that this was only possible in an estate divided society under an enlightened autocracy. Democracies, on the other hand, appeals not to ‘that individual’ but to the masses – and Kierkegaard has the deepest mistrust of man when he becomes part of a mass.

Man as Mass

When man becomes a mass the IQ level plummets but teven worse is that a mass is never aware of what it wants. Everybody just follow along no one takes any responsibility. Therefore, democracy is destined to become the worst tyranny of all. In a democracy the individual will fear the reaction of the masses to such an extent that it will become impossible for him to make his own decisions and take on his own responsibility. This will make it impossible to become a man and, hence, a Christian.

Kierkegaard blamed the church that it had not called to order and torn the mass apart. Instead it joined the mass and became just as ‘democratic’ as everybody else. This criticism of the political development in Denmark became a very intensive and bitter part of the last seven years of Kierkegaard’s life.

The Church Storm

Parts of Kierkegaard’s criticism of the church also had to do with his analysis of Jesus. Of the preachings of Jesus one may say that, on the one hand, there are no limits to the gentleness of Jesus while, on the other hand, there are no limits to his demands and rigor. What Jesus does or represents is always absolute and infinite.

Thus, Jesus acts in a dual role and Kierkegaard cannot get a grip on how the two roles relate to one another and how one can claim both at the same time. But perhaps the answer is that Christianity lives in the tension between the two ultimate demands. Therefore, it represents a destruction of Christianity if one exclusively refers to the one and Kierkegaard became increasingly convinced that this is exactly what the church has done. It has forgotten the rigor of Christianity and distorted Christianity into a soft and cuddly sentimentality.

This church storm of Kierkegaard was a public spectacle like no other and fought with full intensity from Kierkegaard the last seven years of his life right up until his death on November 11th 1855.

Final Remarks

With those words ends this introduction to Søren Kierkegaard. I hope it has ignited an interest in Kierkegaard. He is a treasure house of positive outlook. Obviously, theists will find much in his writings that can inspire but also the atheistic thinker can find much of value in his writings. Particularly, his thoughts about ‘choosing oneself’ and ‘choosing society’, to value ‘attitude over feelings’ and ‘finding eternity in the present moment’ are profoundly inspirational. Moreover, his belief that a deep experience of despair is necessary before one can make the leap from the aesthetic to the ethical can light a beacon of hope when life is hard and existence seems impossible. Because it is precisely there one can make a leap to a new realm of existence.

For another great writer on the human soul jump to this article on Ernest Becker and his 1974 Pulitzer Prize winning book “The Denial of Death”. This was written more than 100 years after Kierkegaard and in many ways builds upon and expands Kierkegaard’s legacy and teachings.

For more articles on existentialism also see my other blog posts on the terror of death, personal freedom, existential isolation and meaninglessness.

The Skeleton-Man Show Death: The High Price of Living

In my new show Death: The High Price of Living I introduce the audience to the existential tradition. You can find more information about the show here that is specifically targeted educational institutions and companies, for instance, as a fun and engaging event at the yearly company art club assembly.

For BOOKING please contact info@skeleton-man.com